by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

It is snowing outside today, a rare sight on the south coast of the UK. Rarer still would be for the snow to settle and stay, but some of the flakes do seem to be staying on the ground. The temperature is down a good 7 degrees since yesterday, and is expected to fall further during the day. I used to despise snow for the sheer inconvenience it perpetually brought when it fell in my hometown; sludgy roads, icy backstreets, and freezing fingers that became unpleasantly prickly and hot upon entering the warmth of home.

I feel differently about snow now. Maybe that has something to do with the fact that it never becomes an inconvenience where I live now, so I needn’t worry too much about perilous footpaths or ice-rink roads. I enjoy its quiescence, how it falls so soundlessly and gently unto the earth only to be sucked up by the moistness of the ground, each flake only whole for a fraction of a second. It is poetry to watch snow fall, to watch it grace the skies and ground with purest white. No landscape compares with that which is coated in a gleaming mass of untouched snow. It makes our known spaces unrecognizable and new once again, just begging to be walked upon and explored afresh.

As I watch the thin snow drift and melt outside my window, I marvel at the beauty of winter. Does witnessing the death and rebirth of a terrain so viscerally make one’s written depiction of a landscape and its seasons all the more earnest and, potentially, beauteous? To observe long winters giving way to almighty thaws that reveal the virgin ground once again must surely be the greatest metaphor for hope there is. The fact that after a never-ending hibernation there is still life, still promise of light after dark. Winter is a season ripe with imagination for both the beautiful and the horrifying, surrounding us as we coop ourselves up in our safe, warm houses while storms and blizzards obliterate the world outside.

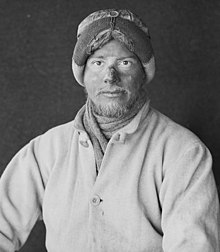

Many writers have capitalized on the cold as a realm for the greatest storytelling. But it is also a place where terror and danger are rife. Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir ‘The Worst Journey in the World’, based on a failed South Pole expedition under Robert Falcon Scott, is one tale that illustrates the merciless force of the cold against the human. The ‘Worst Journey’ that Cherry-Garrard describes is not the South Pole escapade, which he later recounts, but in fact refers to the special expedition of 1911 which had the aim of journeying round the coast of Ross Island (Antarctica) from the group’s western base all the way round to the island’s most easterly point. The team’s goal was to investigate the embryos of emperor penguins in order to investigate a possible connection between the evolution of birds and reptiles.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard in 1912. Photo: Getty Images.

This excursion went horribly wrong. Cherry was tasked with bringing the group’s dog-team to meet his comrades – Scott, Edward A. Wilson, and Henry R. Bowers – in order to help them back to base after they had made their way up to the South Pole. This meeting never occurred as Cherry did not manage to get to so-called ‘One Ton Depot’, which stood a mere 18km from Scott and his team. Consequently, the waiting men froze to death in their tents, where they were eventually found by Cherry and another expedition group some time later.

Cherry-Garrard’s story is a terrifying chronicle of the fragility of human life, and the cost of exploration upon hazardous terrain. Most of the text feels like an extensive apology from Cherry to his dead companions, with attempts to justify the actions he took during that fateful trip. But it is Cherry-Garrard’s haunting descriptions of the absolute hostility of the landscape that fascinate me. Every time he focuses in on the pastoral, it seems as though color has faded from the earth, leaving only the blues and whites of the deep freeze. This land is eerily quiet and oppressively dark, a land made for the horrors that unfold in the pages of Cherry-Garrard’s narrative.

But winter can be delightful too, and the dark silence of its long months can make for the most wondrously imaginative stories, borne of the necessity to dream when times are at their coldest and harshest. Tove Jansson’s ‘The Winter Book’ is a fantastical collection of wintertime stories, each feeling like an entrance to a different secret world.

All of the tales are framed within Jansson’s characteristically direct style of writing, which I first encountered when reading her ‘Moomin’ book series. Even in the most bizarre, otherworldly, and downright strange situations, one finds oneself grounded by Jansson’s awareness of the importance of the familiar and seemingly banal aspects of life; food, childhood obsession and stubbornness, and the mundanity of city life all play a part in Jansson’s stories, even in her fantasy tales. Not all of the stories in ‘The Winter Book’ are set in winter, and the whole thing is a bit of a mishmash of autobiography and fantasy. But those that are placed within the bleak gloom of the Finnish winter depict a deeply humbling appreciation for the cold landscape. One of the stories features a child who becomes fascinated by an iceberg and ends up believing that it must be following her. During one freezing winter night, the little girl goes to visit the iceberg, which is lingering on the shoreline, and notices that it has a small opening inside. She figures that she could very well sit inside the iceberg and journey far from home to find adventures and new lands, but loses her nerve at the last minute and decides against such an escapade. Instead, she puts one of her father’s flashlights into the cavern and pushes the iceberg away. She then watches it float, illuminated, into the dark ocean like a beacon of hope, and dwells on the image when she returns to bed, angry at herself for not having taken this boat-to-nowhere.

Moomin Characters by Tove Jansson

Most of Jansson’s stories in this book center around loneliness coupled with a fervent desire for escape, emotions that are often emphasized by the vastness and solitude of Finland. Jansson was a shy woman who became increasingly anxious as a result of the celebrity that her Moomin books brought her. She craved anonymity and peace from the world of fame that she had unexpectedly found herself in, and took to intermittently escaping from her home in Helsinki to Klovharun, a miniscule island off the coast of Porvoo in the Gulf of Finland. It was here that she would spend as much of the year as she could, save for the depths of winter where the island became nay impossible to live upon. She built a small cabin on the uninhabited island, and later took to bringing her lifelong lover Tuulikki Pietilä with her there to reside for months on end, fishing, building, and reveling in the silence of the landscape.

Jansson’s cabin on Klovharun, Finland

It is perhaps here, on Klovharun, that Jansson’s story ‘The Squirrel’ takes place, a tale describing the unlikely partnership between a woman (Jansson) living alone on an island, and a squirrel that happens to find itself there through unknown means. The story feels isolated and lonely, sentiments exacerbated not only by the cold November that the story is set in, but by Jansson’s various allusions to her need for human company and her desire to sleep as much as possible in order to escape the pains of living. Yet, the bond that forms between Jansson and the squirrel during that winter is effortlessly human and achingly poetic. However, during the course of the story, the protagonist begins despising the squirrel more and more for its ability to live on the island while, prior to its arrival, she was the ‘only’ other thing living there. The descriptions of resentment, jealousy, and hostility that Jansson assumes throughout the narrative suggest how very alienated and intimidated she felt in the presence of others. The story ends with the squirrel sailing away from the island on Jansson’s own boat, to which she says ‘“You damn squirrel,”…softly, in admiration’. She realizes that she admires the squirrel for embodying the same qualities as she; a penchant for escape and adventure, and an independent nature embodied in solitary existence. Once the squirrel has gone, Jansson goes back to her quiet cabin life, while ‘Outside it had begun to snow, heavily and peacefully – winter had come.’

The Cat

The snow is still falling outside my window. Tiny flakes float around the panes and onto the steps in the garden. Sometimes, they fall faster and more erratically, while at other times they seem to remain afloat, going up and down and up and down until they decide to give up and collapse upon the floor. Only a small amount of snow has stayed since it started falling, coating the streets and parks with a thin, wispy coat that flicks up in little flurries as one walks through it. I imagine a coating as high as a boot pressing itself against the doors and crowding up the walls. I imagine the pebbles on the beach to be completely obscured by thick blankets of the stuff, and the sea to have become entangled in sheets of ice across its surface, stretching towards the horizon. The wind is blowing hither and thither, shaking the branches of the naked trees and whistling through the blades of grass and early daffodils. All is still and silent, save for the occasional wild gust that echoes in my ears, and the distant rumble of trains passing, unseen, behind my garden. Now a robin has begun to chirp its brisk, lonesome song, breaking the quiet and piercing the white clouds above it. I wonder whether birds feel the chill that I do when I go out into the bitter cold. When I leave my home, my toes and fingers begin almost immediately to seize up, tingling in anger at the cold even under the warmest socks and gloves. Do birds feel this cold hit their tiny feet as they cling to the branches and sing? Do they feel the icy breeze ruffle their feathers, and does it seep into their bones as it does mine?

It is warm, here, inside my house. There is a pot of dried, dead roses in a glass jar on the table I am sat at. I haven’t the heart to throw them out. Besides, I think flowers are most beautiful when they curl and crumble, when their leaves turn into crisp, fragile sheets, and their heads look downwards, humbly acknowledging the end to their reign of beauteous splendour. If touched, they fall weightlessly to the table, and all memory of thick buds filled with water and sun are forgotten. Yet all the while, the daffodils outside continue to bloom under the heavy frost and dark days of winter.

A cat came to my door yester morning. I’d seen him before, a timid thing that slinks underneath the cars on my road when one walks by. I saw him on the garden steps when sat in this very spot, and he looked at me through the glass, then miaowed too softly to be heard. I went into the kitchen, placed a small lump of butter onto a dish, then ran upstairs to open my back door. The cat ran to meet me, though rejected the butter after a few haughty sniffs. I reached out, hesitantly, to stroke him, and was met with his butting nose. I traced his body with my hand, brushing off the snowflakes and feeling his warm flanks beneath my fingers. He placed a nervous paw into the house, glancing into my face as he did so. Once certain he wasn’t to be reprimanded for doing so, he jumped deftly onto the blue carpet and began nuzzling any corners he could find; the radiator, mirror, hat-stand, floor – all were good instruments for him to rub himself emphatically on. He was emitting a loud purr by this point, and miaowing sporadically as he welcomed my touch. All of a sudden he lashed out, cutting the forefinger and little finger of my right hand, then leaped out of the door he came from back into the snow-covered grass. I watched him as I bled onto my knees. He looked back at me through the glass door. We kept this state of feud for some minutes, until the cat bowed his head and walked away.

============

Carl Kruse Blog Homepage

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Hazel Anna Rogers also wrote how she became friends with winter.

Her last blog post was psychogeography, maps, borders, paradise.

Carl Kruse is also on Buzzfeed.

OMG! I love Tove Jannson’s books!

Yay! Another fan!

Carl Kruse