by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog

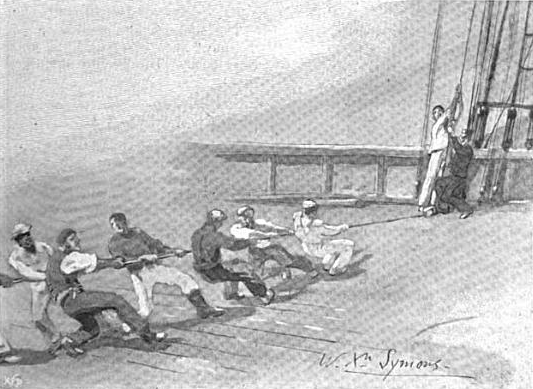

“… I soon got used to this singing, for the sailors never touched a rope without it. Sometimes, when no one happened to strike up, and the pulling, whatever it might be, did not seem to be getting forward very well, the mate would always say, ‘Come men, can’t any of you sing? Sing now and raise the dead. ‘

And then someone of them would begin, and if every man’s arms were as much relieved as mine by the song, and he could pull as much better as I did, with such a cheering accompaniment, I am sure the song was well worth the breath expended on it.

It is a great thing in a sailor to know how to sing well, for he gets a great name by it from the officers, and a good deal of popularity among his shipmates. Some sea captains, before shipping a man, always ask him whether he can sing out at a rope.”

— Herman Melville, “Redburn”, (1849)

I started finding them on social media, from Tiktok to Instagram, and they got into my head and I hummed them all day. It could have been that melancholy rhythm, dragging itself verse after verse, constant yet never rusty, or perhaps the idea of catching the ancient melodies of a forgotten time, compositions that have crossed the oceans for centuries, that when reaching my ears compelled me to sing. Sea shanties have something in common with the ancient spells of a dusty magic book: combinations of sounds, rhythm, and words that remain sealed in time and, over the years, enriched with a sublimated sacredness capable of evoking in us images offuscate, reconstructions of a past that we have never lived.

Sea shanties are traditional folk songs, usually composed and sung by sailors during voyages. This music has accompanied seafarers for centuries, probably finding its beginnings in the percussion sound of the drums with which the rhythm of the oarsmen was timed. But sea shanties are different from other sea songs: first, they are characterized by a heavy rhythm, that always remains the same, even if the words themselves might change. And they are different also in form: traditionally, these are “back and forth” songs, meaning that we have the main singer, known as the shantyman, guiding the others in the song, pronouncing the first and the third verse of the stanza; with the choir answering his calls, and joining in the second and fourth verses of the stanza.

Sea shanties are born as songs that accompany sailors in their jobs onboard, group tasks or actions, like cleaning, repairing sails, and such. Music kept them company, and allayed boredom during long hours of usually repetitive work.

How the Sea Shanty originated is not difficult to discover. It has undoubtedly grown out of the natural Inclination one feels in hauling, or in otherwise performing any rhythmical operation, to keep time with one’s voice, feet, or hands, in parallel rhythmical sound.

— William Saunders, “Sailor Songs and Songs of the Sea”, 1928

The term “sea shanty” began to appear in the late 19th century. Many scholars have assumed that there is an analogy with the French term “chanter”, which means “sing”. Others assert it traces back to the English word “chant”. Others argue that it refers directly to the lyrics of some songs: for example, North American lumberman songs often begin with the verse “Come to all ye brave shanty boys”.

One possible explanation can be found exploring “the empire where the sun never sets”: in the 19th century, England also dominated India, the homeland of Hinduism and Sanskrit: a language, like Aramaic, where words are formed by specific vibrations; where sound and form are the same, sound and sensation are the same, and where the repetition of a sound cyclically allows the manifestation of that form.

The Sanskrit word Śānti (usually anglicized in Shanti or Shantih) indicates a state of absolute inner peace and serene imperturbability, characterized by the absence of the frenetic thought-waves (vritti) generated by the mind. The Mantra Om Shanti means peace in mind, word, and body. The vibration of the word peace is the sound Sh. Peace in Sanskrit is called Śānti. In Hebrew ancient peace is said Shalom, in Sanskrit Śānti, in Aramaic Heshusha.

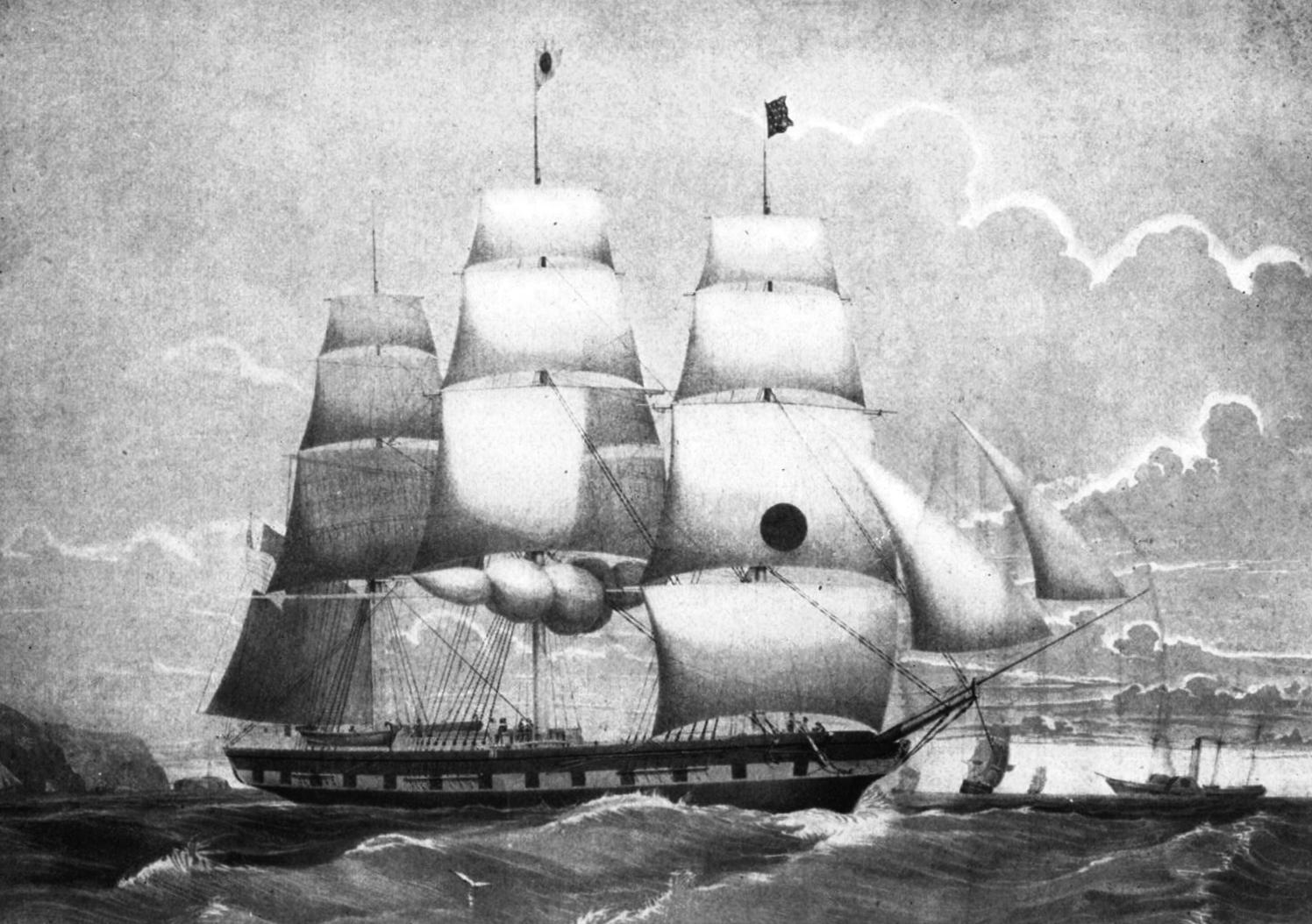

According to some historians, the first sea shanties should date back to the 16th century, although their maxim of popularity supposedly was in the 19th century. Others, on the other hand, argue that sailors began to sing the sea shanties after the Napoleonic Wars (between 1830 and 1870), with the expansion of transatlantic trade, and with the consequent construction of larger vessels, faster and with more wood.

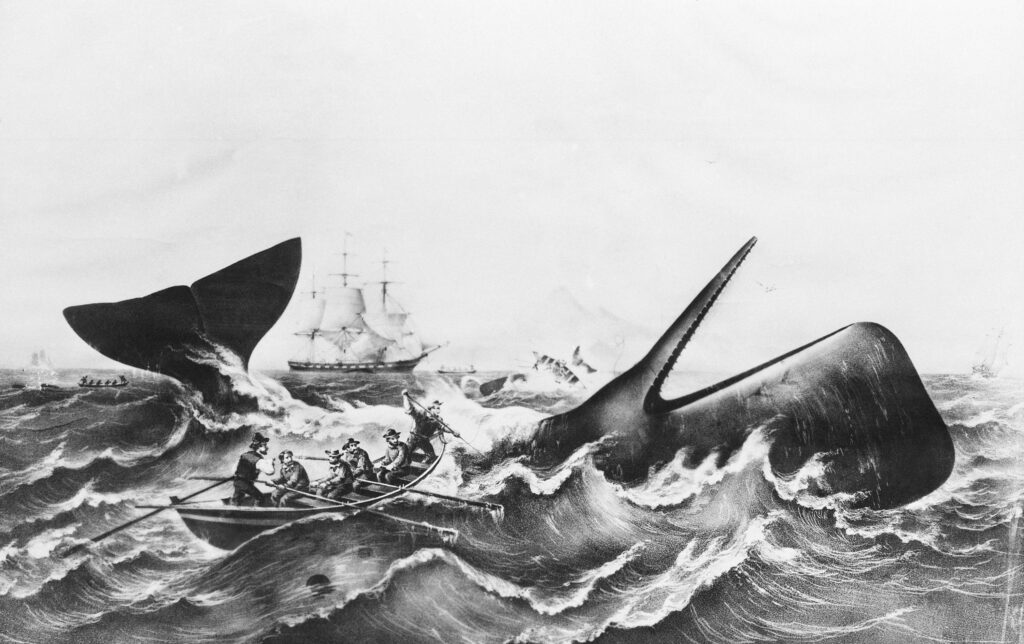

Historian Kate Jamieson explains that sea shanties took place mainly in merchant ships, and for this reason, themes such as whaling are recurrent.

Merchant ships required large crews, which had to coordinate loading and offloading cargo,hauling ropes and setting sails, repetitive activities, long, and often boring. Music made some of the tedium more attractive, fun; on the rhythm of the music the sailors coordinated, the time seemed to pass faster and hours were lighter.

The purpose of a hauling shanty was a rhythm to the task of extracting just that last ounce from men habitually Weary, overworked, and underfed.

— Harold Whates, ‘The Background of Sea Shanties’

Of course, there were different types of sea shanties: sung in French, English, American, and Australian ships. The different versions of sea shanties were born and structured without referring to an identical model for all, but building each its musical tradition (for example, Le Capitain de San Malo).

The influences are traced in the history of the sailors themselves: popular melodies, in particular those of Ireland and Scotland, but also the African melodies and songs, which were tuned by slave stevedores who sang as they piled bales of cotton.

Sea shanty texts are simple, interchangeable, and give space for improvisation. A word from the chorus is emphasized, to mark in the rhythm the moment when sailors coordinate towards an action, such as lowering the top or performing a maneuver.

With the rise of steamships, the rhythm on ships accelerated, and with the automation of different tasks, the need to lighten the repetitiveness of work diminished, and so the sea shanties.

“Some of the songs I have quoted seem foolish now that they are written down. They are not the sort of songs to print. They are songs to be sung under certain conditions, and where those conditions do not exist they appear out of place. At sea, when they are sung in the quiet dog-watch, or over the rope, they are the most beautiful of all songs. It is difficult to write them down without emotion; for they are a part of life. One cannot detach them from life, One cannot write a word of them without thinking of days that are over, or comrades who have long been coral, and old beautiful ships, once so stately, which are now old iron. “

— John Masefield in Sea Songs 1

==========

The blog homepage is at https://www.carlkruse.com

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

The last post in the blog was Curiosities from the Theater of the Absurd.

More on Carl Kruse. Kruse is also on Vator.

Well…hmmm…kinda of a cool read. Didn’t expect this from sea shanties.