by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

When I was young and being driven somewhere or other, I would always notice and ponder the physical space between signs indicating where we were arriving at and where we had left from. Often, a sign is placed at the entry to a new borough or township, then when one leaves said named space, the same sign is placed on the opposite side of the road, this time with a diagonal cross over the place name. This cross indicated our departure from named space. I used to consider the pastures and houses that would litter the countryside between these named places, and wonder where they were, and how their addresses would themselves address their disparity to the christened spaces on either side of them. Where are we when we are nowhere? Of course, one could naturally name these places by what part of the country they are in, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are, in essence, unspecific, forgotten areas of the land. I think of these spaces as near-mythical lands, fictional entities that are so isolated that they have been neglected on maps. These lands are never trodden upon, only driven over and observed through the windows of vehicles.

To conceive of a space, humanity requires a concrete representation of it through the use of a name. A name signifies the ownership of a land, a human presence that implies hegemony over the pastoral. We need names to navigate and orientate ourselves, and to place arbitrary boundaries between where we are and where we are not. The land itself does not bear any material indication of these psychological borders, except in the form of the waters of rivers and seas, yet we are guided as a people through the lines we write on maps and the signs we place upon the lands we own. The maps we read our world by are mere abstractions from the physical embodiment of the earth itself, a world we have defined by our own anthropocentric determinations of what is important and what is not.

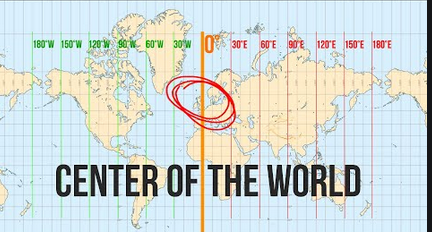

Consider a map, an English map. On it, we see Great Britain in the center of the world, enlarged and prominent to the eye. This map is political by its very existence; it proclaims an England-centric earth where all other spaces can be mapped as north, south, east, or west from our own tiny island.

When I see a map that shifts its gaze to, say, Russia as the central space, I find myself disorientated, and must trace my footsteps back to the British Isles in order to successfully navigate my surroundings. By decentralizing the space that I qualify as my ‘known’ world, map variations show to me my inherently biased perception of the earth. The knowledge I have acquired over years of observing maps is one with foundations of cartographic violence. If I were to see a borderless map, I would know where to split the land masses to create the fickle topographical representations of countries that have been determined over centuries of human history. Yet even the thick, concrete lines of maps are prone to change. Territorial jurisdiction is constantly susceptible to shifts based on the political landscape; the Iraqi-Turkish border was only created by the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab in the wake of the second recapturing of Baghdad by the Ottoman Empire (1638), and the border between Yemen and Saudi Arabia was only established in 2000 (a result of the Saudis claim that a boundary between the spaces was necessary to guard against perceived terrorist threats in Yemen).

By marking spaces out as distinctly separate from each other, despite them often having no physical demarcations outside of maps, we invoke sentiments of hostility against the spaces that are not ‘ours’, spaces that we deem ‘other’ from us through the intrinsically prejudiced abstraction that maps provide us with. To create a map is to make a political statement: that the places depicted as central, or larger than they are in reality compared to other places, have the greatest political importance on the world stage. Cartographic projections can emphasize or understate land masses so as to make statements of their own about the politicization of space; Mercator’s projection, the first map created to facilitate navigation routes by ‘flattening’ the land space, was rejected by James Gall and Arno Peters, who collectively created the Gall-Peters projection. Whereas on Mercator’s projection, much of the land mass is false in size-representation (the US is disproportionally large, Africa too small, and Greenland incorrectly sized as equal to Europe), the Gall-Peters map claims that a five pence piece can be placed anywhere upon the projection, and it will accurately represent the sizes of each space in relation to one another. The Gall-Peters projection is bizarrely nauseous to observe – Africa is elongated, and Europe and the Americas as squashed up at the top of the map. It is unsettling how inexplicably uncomfortable it is to have one’s entire perception of the world reconfigured, and it certainly suggests to me how biased I am in my conception of earth. My eyes and mind have been conditioned to be intrinsically euro-western-centric.

But this bias is universal, and I have at least some comfort in that. The places we grow up in, the streets and cities we know, are our subjective ‘axis mundi’ (axis of the world/center of the world). They are the centers of the psychogeographical universes we create from our known surroundings. I grew up on an island, Great Britain, yet to my eyes it is an island as wide as Russia and as long as South America, because all I see day by day are its skies, its people, and its fields, which span as far as the eye can see. The island of Puka Puka, an atoll in the Cook Islands, is only around three kilometers square in size, a tenth of the size of the parish of Shrewsbury, the town where I grew up. It has about 500 long-term inhabitants, many of which will live there their entire lives. It is unfathomable to me how so small a place can be resident to so many people, people who likely consider their island as their own axis mundi. But I suppose they must do.

We all live on islands, regardless of how small or large these islands are, islands composed of familiar corners and roads that harbor the footsteps of history. We live a secular existence in the places we call ‘home’, an existence defined by vignetted landscapes; the known, or the ‘genius loci’ (sense/spirit of space), and our limited knowledge and perception of the unknown. The ‘unknown’ can often materialize as either a place that is more dangerous or hostile than our own, or as the oneiric view of ‘paradise’. Paradise is, more often than not, a place far from our own, but it can truly mean anything, or anywhere. Its realization is completely reliant on the imagination of its creator: us. Perhaps, for one living a life characterized by the offices and apartment blocks of London, paradise is a dusting of white sand upon a warm, wet body emerging from the turquoise waters of an isolated island. Perhaps, for one living in the lonely southern marshes of Ireland, paradise is the endless hustle and bustle of the city, open with possibility, echoing with the hubbub of busy people. Perhaps.

My ‘paradise’ has changed its cloak many a time. Paradise, for me, has been the palm trees and garish colors of Los Angeles, has been the mountains and lakes of the Midi-Pyrenees, has been the black sand and dry crags of Santorini, has been the elegance and statuesque grandeur of Paris. Paradise changes its form, forever determined by the dreams we have of what lies outside of our islands. Its perennial verdancy shines forevermore, for it is but a dream, a virtually concrete representation of our thirst for escape that doesn’t account for the tribulations that such a paradise might entail if we actually did achieve it. In Santorini, once the summer season begins, its secluded demeanor transforms overnight into a tourist haven, the wind-swept black sand beaches become awash with swollen red bodies, and the sound of waves lapping at its shores is lost and replaced by blaring music from establishments on the sea front, luring visitors in to sup upon their delights. And so, paradise disappears, or must change its form.

Here is my paradise of today. It may change, it may morph as surely as the waves of the ocean do in the wrath of the wind. It may be fictional, or it may have some certain verity in its walls, walls that may always be enclosed beneath my eyes, like the gates of Eden, never to be touched, but always to be yearned for beneath a blanket of sleep:

98° 72’3.42 N, 145° 13’0.85 E

Peflonky Archipelago: 85 kilometres east of Hell’s Sinkhole; 28 kilometres south of Porpoise

It is early spring, and the wind is mild, kicking up flurries of snow as dry and powdery as flour. On the southernmost tip of the island sits a small mökki of 500 square feet. Its body is made of dark Finnish Pine (Pinus Silvestris), and it has one south-facing window and one north-facing. A small cast iron chimney protrudes from the roof and is smoking puffs of black into the morning air. Inside, a set of wooden stairs lead up to an internal balcony, where a mattress and fluffy down duvet are set upon the ground. A large water tank stands in the far corner of the bottom floor facing the wood burner, and a red woolen rug stretches from beneath it towards the center of the room.

From inside, one can hear the tender suck of waves slapping and receding from the rocky inlet just in front of the hut. Green is returning to the land. Lily of the Valley (Convallaria majalis) and Rosebay Willowherb (Chamaenerion) have begun to rear their heads between the rocks and patches of snow, and the dawn feels distinctly warm on the skin.

Life is returning to the land. Three kilometers east of the hut, the train station is being unpaneled from having been boarded up during winter. If one listens earnestly enough, the wheezing of a steam train can be heard in the distance. The tracks are just a few inches below the water, and when the train breezes gently towards the shore the sea splashes alongside it. This train brings people to-and-from the mainland, mainly fishermen and persons who desire solitude in the summer months. This place is unliveable in winter, when blizzards rage upon the earth and the sea becomes a seething grey beast, mounting the shore in splitting cacophony for weeks on end. But come spring through autumn and there is no worthier place to spend one’s time, whiling away the hours writing, foraging, swimming, and drinking.

The sea is a thrilling 2.4° this morning. Its icy blue clarity begs to be interrupted by gasping mortal bodies shouting to relieve the pain of the cold as they immerse themselves. It is water made to remind oneself that one is alive. Upon such a realization, the pre-warmed water of the metal bathtub outside the hut reminds one of the unchallenged superiority of pleasure above all. A clear bottle of aged whisky sits beside the tub, to be consumed during the pleasure bath to warm the cockles, while the water warms the dermis.

Canada geese (Branta canadensis) will soon flock here, along with horned grebes (Podiceps auritus) and nightjars (Caprimulgus europaeus), who will fill the grass and skies once more with song. The snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) can be heard hooting during the pure black nights. I once saw, from my seat by the southern window, a ringed seal (Pusa hispida) heaving its thick flanks onto the beach, where it began moaning, barking, and wriggling in joy beneath the summer sun.

A yellow rowboat is sat upon the sand a few meters from the mökki. Its canary veneer is crumbly, but the name plate remains readable: ‘Paradisum’.

==============

Blog Homepage at https://www.carlkruse.com

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

For another take on psychogeography check out Fraser Hibbitt’s post.

The last blog post was an ode to Irish playwright Samuel Beckett.

Carl Kruse is also on Medium – his latest article is here.

Out the door and there you go!