Samuel Beckett’s Self-conscious Game

by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog

A performance should appear effortless and unscripted. The long hours of practice transmuted into a rare vision is the process of artistry. On with the show and it is seen for the first time like a lived experience. Belief during the show is different from belief after the show; as with all events, time grants reflection, and reflection can make much of any given plot. This ability to make viewers reflect has given the stage a history of very serious thinkers: Tragedians of ancient Athens were teachers and a performance enabled them to teach, to show; playwrights down the centuries have mostly agreed on this point. The role of performance itself takes a curious turn in Samuel Beckett’s theatricality. It is obvious that Beckett wants to show something, but at the same time, he is at odds with the form in which he is showing it. Beckett’s tense theatricality has, oddly enough, not marred the performance of his plays.

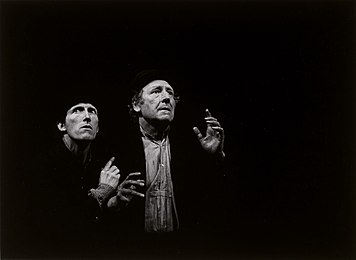

Some talk on Beckett’s famous plays will serve the point. “Waiting for Godot”, the play where nothing, event-wise, happens saw much critical abuse; later, termed a masterpiece and icon of the ‘Absurdist Theatre’.

Source: Wikipedia

The characters, Estragon and Vladimir, wait for someone (something?) called Godot who fails to appear. The audience perhaps feeling that they were being duped as the duo on stage amuse themselves for the length of the play in witty, understandable to them, dialogue. The whole ritual of going to the theater presumes that the viewer will follow and make meaning out of the events. The audience sits there waiting and construing the strange scene whilst the actors fidget with language and their bodies, waiting also for Godot.

It is difficult not to analyze the play in terms of some bleak existential condition. We all wait for some kind of ‘meaning’ which eludes us – we play around and then depart. The performance seems odd, nonsensical, only in relation to our rich cultural history of plays that have discernible sense. In struggling against these sensical forms, Beckett realized that the process of struggle reveals something of substance: Of meaning being in the struggle for meaning. If the ornament of reliable story-telling leaves, it doesn’t mean humanity leaves with it. In fact, it offers a fresh view of the human in rags, still delighting us with a subtle wisdom.

Beckett’s later play Endgame is again of this vein; the course of meaning is denied to run smoothly. Here, however, the characters appear self-aware of this predicament. One of the main characters, Hamm, speaks: ‘An aside, ape! Did you never hear an aside before? (pause.) I’m warming up for my last soliloquy’.

Although the ‘breaking of the fourth wall’ is nothing new in theater, it strikes with particular force in this play. It signifies this self-conscious game which Beckett is playing. He knows the ‘rules’ of theater, of narrative, and invites them into the game as a player, not as the game-master as we would expect these ‘rules’ to be.

Endgame, as the title suggests, is a play about how to end, how to conclude and reach resolve. It is while this game of endings is occurring that the human quality of humorous suggestion and ambiguity is observed. The very idea of performance is wrestling with the characters’ ambiguous search for their role, and therefore, resolve. Beckett’s character seemed to be hounded by the demands of the play, self-conscious of their tentative roles, their lack of insight. Yet time and time again, in Beckett’s plays, despite the ‘stripping away’ of traditional dramatic structure, and the character’s ambiguous situation, we are brought vis-à-vis with a comprehendible human essence; an actor not understanding their part, mouthing words and shuffling about; playing.

——

Eugene Ionesco’s ‘swelling’

Ionesco leads an audience from a fairly reasonable point of view to one in which things swell beyond proportion. This idea of ‘swelling’ is what we have come to expect from any stock narrative: the plot ‘thickens’; interests, desires and chance, begin to cause frustrations and consequences. Ionesco adheres to this ‘swelling progress’ in several plays to lead the audience on. However, the ambiguous and ‘absurd’ nature of Ionesco’s plays leave, at first, only this idea of swelling, something we may be more unconscious of in the act of reading or watching a movie.

Ionesco utilizes an increasing intensity to point the audience in the direction of his meaning. A good example would be his play The Lesson. In the play, a pupil arrives at a professor’s house. He begins to question her on a number of mundane and basic questions that the pupil, being eighteen, we would expect to have on rote memory. She does well and the professor is congratulatory. The lesson begins to become fraught with misunderstandings between what is actual and what is theoretical:

Prof: Good. I stick yet another one on. How many would you have?

Pupil: Three ears

Prof: I take one of them away … how many ears … do you have left?

Pupil: Two.

Prof: Good. I take another one away. How many do you have left?

Pupil: Two.

Prof: No. You have two ears. I take away one. I nibble one off. How many do you have left?

Pupil: Two.

It goes back and forth for a while with the professor trying to make the pupil understand subtraction in examples like this until it becomes more and more abstract. The lesson turns to language with more theoretical ambiguities, ambiguities about what each other are saying and how they can even communicate. The pupil begins to complain about a certain toothache which is exacerbated by the lesson – contrary to the pupil’s toothache, the professor becomes increasingly tyrannical. The increasing intensity of the inverse relationship between the two results in the professor murdering the pupil. The last piece of dialogue is of the professor’s maid who is ushering in a new pupil. A repetition of the events of the The Lesson is implied.

Ionesco is a master of mood, and it is this gradual swelling which he chooses to perform for him alongside his actors. The verbal complications of The Lesson become exasperating until exasperation is the only thing the audience can focus on, isolating a kind of obsessive, encompassing mood. The audience will look for the human meaning in the performance: the interaction between the characters, the meaning of the plot, but it shouldn’t go overlooked that Ionesco wanted to represent ‘a mood and not an ideology, an impulse not a programme’. However ambiguous the dialogue and actions appear to be, the intensity of the ‘swelling’ informs the viewer. Ionesco even uses the ‘swelling’ to perform a role in his play Amedee where the strange thing festering and growing in the spare room of Amedee’s apartment is used, in the end, as a kind of balloon to fly Amedee away from the dramatic action.

Short Reflection on Adamov’s Change of Heart

Not as well-known as the previous playwrights, but offering an interesting cause for reflection. Arthur Adamov started his playwriting career in the Absurdist camp. He then began to follow in the footsteps of the pre-eminent twentieth century playwright Bertolt Brecht, known for his unflagging efforts to inculcate a kind of theater which would make the audience reflect on society, especially capitalist society. Adamov’s absurdity was Kafkaesque. His reality was a vision of individuals unable to come to terms with any objective reality outside of themselves. Anxiety ridden and incomprehensible, society seemed to mock the individual.

In his Professor Taranne, a supposed renowned professor is accused of indecent exposure. In his quest to prove that this is false, Taranne is met with one absurdity after another: people are unable to recognize him; he cannot read his lecture notes; his lectures are said to be plagiarized. The play ends with Taranne looking at a seating chart of where he is supposed to be sitting aboard a liner, a chart that is completely blank – the final action is of him beginning to take off his clothes. When read, the play feels eerily familiar. It appears to be following the ‘logic’ of a nightmare, a nightmare about identity crisis and social anxiety, in which an undefined guilt pursues Taranne into insignificance.

Why the change of heart? It appears, after writing out his personal neuroses, Adamov felt compelled to write ‘Realistic’ plays; plays with a clear narrative and, following Brecht, directed towards raising social awareness around political issues. It raises the question of dramatic efficacy – which form realizes a message, and will leave a lasting impression.

Martin Esslin, the critic who took pains to elucidate the ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ speaks about a style common to much of the Absurd drama. He speaks of Absurdism as portraying a ‘poetical image’, an image that is polyvalent in meaning, and it is this polyvalency which provides a certain atmosphere, or ‘mode of being’. The ambiguity of Absurdist theater is predicated upon the lack of clear meaning provided by existing. They do not believe in a well-ordered universe or even, at times, reliable communication. If this is true, then the Absurdist playwright would be the new ‘Realist’. Adamov obviously thought not – it was only a method to express anguish and incomprehensibility, something to be overcome and discarded.

Yet, as Esslin entreats us to believe, something is happening in these plays. There is movement and a mood to them. The absurdist camp has a kind of freedom from form that allows it to probe society in a profound and versatile manner; an ability to portray a polyvalency of meaning around existing which society often denies. In fact, the implicit satiric bite that Absurdist drama offers shouldn’t be overlooked. Their favorite targets of domineering intellectuals, aggressive tyrants and deluding bureaucracies, are arguably more easily ingested by an audience than a political lampoon.

If Absurdist theatre, out of negation, creates a dramatic image of irrationality, despair and anxiety, it is also seeking a kind of affirmative. For the Absurdist play is, of course, a re-enactment, a space where we learn something about despair, irrationality and anxiety – It is a kind of conquering of these lamentable states. Through its tortured techniques, we are provided with the rich imagery of the absurd world. Sheer incomprehensibility can serve the playwright well for an expression of ridiculous politics, social depreciation or the individual at odds with their society. If writing Absurdist plays signified his personal neuroses, then perhaps Adamov wished not to return to hell. Yet it would be foolish to think only the anguished are drawn to the absurd. It has the indomitable power of laughter about it, and the sense of a modern poetry. Although Adamov changed his heart, we might point out that he was wise enough to use, in his later realistic plays, fragments of that which in his youth he suffered to write; fragments of absurdity which, fortunately or not, foster an expressive currency.

The homepage of this Carl Kruse blog is here

Contact: Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser Hibbittt include Reflections at The British Library

Fernando Pessoa: Alchemist of Sensations and the Notebooks of Pan’s Labyrinth.

Carl Kruse is also active on Goodreads.

I’ve never understood the absurdists but perhaps that is the point?

Could be one of the points. A reflection of the purposeless of life or at least our ability to detect purpose.