by Fraser Hibbitt for the Carl Kruse Blog

Every year, writers from around the world submit their entries to the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest; the prize is a pittance, but the winner does get their entry published in the anthology which has been steadily growing since 1983. The rubric is simple: successfully write the worst introductory paragraph to a novel. Other Bulwer-Lyttonesque competitions now take place to commemorate poor artistic achievement, like the Golden Raspberry Awards (movies) – although the Bulwer-Lytton has the difference of being organized around purposely creating poor quality writing, rather than scanning culture for remarkable flops as the Golden Raspberry Awards does. Anyhow, these competitions, and other related commemorations, take pleasure in artistic failure and even go to great lengths to celebrate it, organize it, and in a manner, ritualize it.

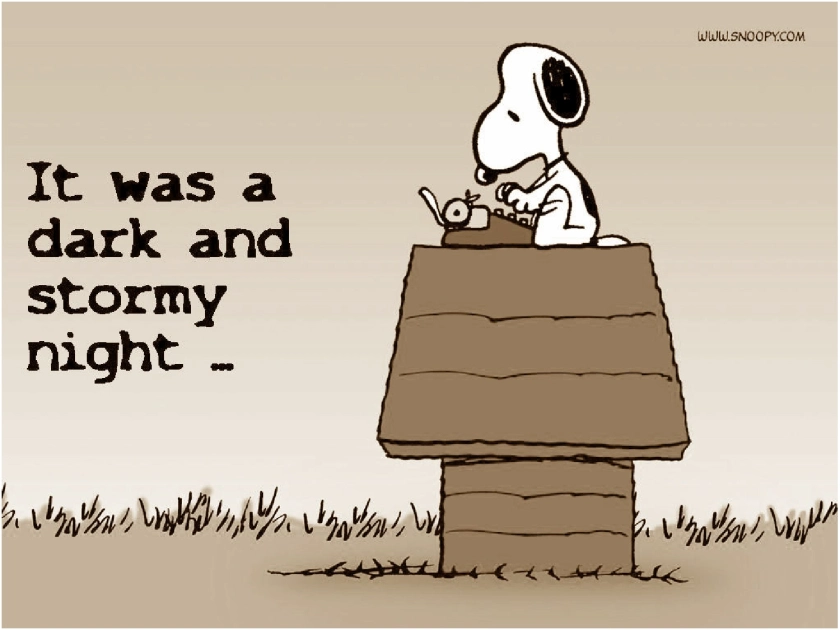

The Bulwer-Lytton anthology is a rather small affair in comparison to the pomp and satiric mood of the Golden Raspberry, but they are both pointing to this want of celebration – if you’re wondering about the name “Bulwer-Lytton”, it is out of respect to the 19th-century writer and politician who began a novel with the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night” and proceeded to continue, eyes averted to his own inelegance. There is a whole host of mock awards that are vaguely related to this theme of celebrating failure: The Darwin Awards (a foolish, or avoidable mortality, “selecting themselves out of the gene pool”), the IG noble Prize (unusual or trivial scientific research), the Golden Fleece Award (to the most outstanding wasteful use of government funds), the Foot in Mouth Award (a peculiar juggle of nonsense uttered by a public/cultural figure), etc.

As soon as someone thinks to categorize, or “this ought to be remembered”, then reference can never be too far; a handy index keeps things in place. Indexing failure perhaps is humbling: who knows what little nervous tick will trick you into nonsense, when time will play a little joke. Perhaps more importantly, the contests are just some fun at others’ expense. It’s funny to read what Donald Rumsfeld said: “We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know”.

The pseudo-ritualistic events, mostly from the last thirty years or so, still preserve the memory of these acts in the same way an inscribed trophy holds its champions. Only, these events are coloured by irony. They are purposely satirical, mock-formalised, and “serious” about their program. The event seems to take on the act, faux pas or failure, that they are celebrating. If the whole mood is ironic, then it cannot be held accountable because they don’t mean what they mean; this seems the best way to celebrate failure. It doesn’t have the “right attitude” tension that empowers an event of importance. In some cases, this philosophy has been taken very seriously: The “Not Terribly Good Club of Great Britain” celebrated those who had a flair for failure and ineptitude. The handbook of the club, The Book of Heroic Failures, became a best-seller with its author, and founder of the club, Stephen Pile, being deposed as president for his lack of heroic failure with the book – the club was then disbanded. It is somehow not fitting to grant failure the canonical respect of forced gestures, instead, it must be preserved with an embodiment of itself.

Excessive irony is moribund and quickly becomes vacuous, everything being levelled, resulting in ambiguity. However, what comes to mind when Kierkegaard speaks of irony as a “concealed enthusiasm”? Irony of this kind is the result of sacrifice, of a higher kind of internality, as one learns after failure. To become ironic in this sense is, then, to not only have an “enthusiasm” of self, but, by degrees, perhaps a greater connection with what is meaningful, and worthy of praise. This may be overshooting things, but it is difficult to believe that, having faced the humiliation of failure in whatever, perhaps your dreams, on second thought, a greater respect for, and a better understanding of, the ways of the world would not flourish.

Great and noble actions, the pinnacles of artistic powers, bend culture into genuflection because they actually shape cultural attitudes and even ideals. There is no doubt that discussing, reflecting on, and challenging these great actions or creative powers is one way of questioning a cultural attitude. However you have it, it is, generally, here where embodiment ought to take place; embodiment, imitation, and the desire to preserve such things. This is no easy metamorphosis and failure is always waiting, laughing in the wings, gesturing absurdly at the actors before their all-too-important stint on the stage. Of course, the actor expects it and has probably said to themselves a thousand times that well-worn piece of received wisdom that failure is just as important as success.

The commemorations of failure and work of poor quality attend to the confrontation between the individual and their life in the negative, bringing all that is worthy into sharp relief. Failure has some of the same alluring quality as great work: “well, if they did that! … why don’t I put myself out there?”, and then, funnily enough, they are in process of failing. They have been tricked at the expense of another and set themselves up for their own fall because another piece of received wisdom comes along to inform them that failure is integral – “look how hard we’ve all tried to keep things tight, respectable, and seemingly effortless; where do you think this came from?”.

An example of someone knowingly failing does not easily come to mind and that is because to do so would be, like the pseudo-ritualistic award ceremonies, ironic; it would not channel that actual psychological fact of failing. Failure has the combination of that strict seriousness which undermines itself and usually this aids someone in their experience. Usually, however not always. The 19th century Scottish Poet William McGonagall was notoriously unaffected by the criticism levelled at his poetry, i.e. that he was deaf to any kind of metaphor and, by the sound of his verse, did not bother about scansion. He is remembered fondly, but not in the way Robert Burns is.

The unexpected, awkward finesse of cultural failure withstands because it points to the un-artificial; it has no words to prevaricate, no action that can undo; it is a quick judgment of usually small proportions; the lights do not go out, and no stage mocks relentlessly to death; it is not that life does not continually mock us for our gross misunderstandings, but rather we come to expect them after a few blows of consciousness. Noble Roman-like busts line the wall at a great library, portraits of you-ought-to-know have as their home an entire wing of a gallery, ear-marked books of savour and courage remain on the shelf, and the reason is quite clear and obvious; and where is failure? Laughing in the obscurities of the heart, and occasionally cheered on at a ceremony of little consequence.

===========

The Carl Kruse Blog homepage is here.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser Hibbitt include ChatGPT and Curiosities from the Theater of the Absurd.

Find Carl Kruse on the Ivy Circle and on the Alumni Blogs of Princeton University.

Oh hey! I don’t find “it was a dark and stormy night” a bad way to start at all. 😀

Essential that you do you. 🙂

Carl Kruse