by Fraser Hibbitt

There is a myth from Ancient Greece – containing a well-known proverb that reverberated in Greek thought. It involves the creature Silenus, the teacher of the wine god Dionysus. In his drunken state, Silenus was possessed by sacred knowledge and prophesy. A version of the story runs that the King of Phrygia, Midas, eager to learn from Silenus, caught him in the woods and plagued him with the burning questions of “what is the most desirable thing among mankind?” and “who is the happiest of man?”. Unwilling and silent, Silenus finally replied: “why do you compel me to answer that which it’s far better you remain ignorant? For those knowing not their misfortune live with the least worry. As for humans, it is best for them not to be born at all; if born, the next best thing is to die as soon as possible”. So much for the wisdom of Silenus.

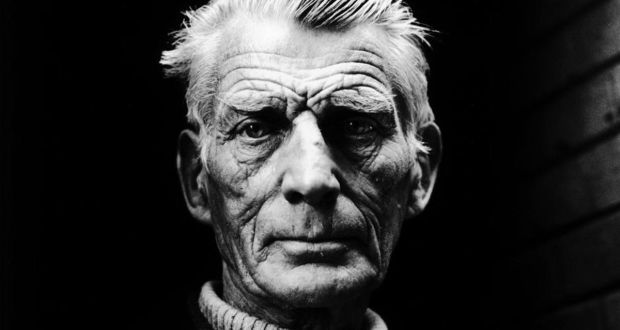

This position would resurface in the nineteenth century through the voice of the influential German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. He endorsed the view, finding the world a never-ending cycle of suffering. The wisdom of Silenus, as told through Schopenhauer, would be transformed in the oeuvre of the astounding Irish writer, Samuel Beckett, to something we can embrace and even laugh at.

Since his early twenties, Beckett had suffered from intense anxiety attacks, awaking to the swift pounding of the heart and a terrorful state of near paralysis. Finding no answer from the doctors about his heart, he moved to London to undergo psychoanalysis in hopes of understanding his anxiety. He attended lectures of the great Carl Jung and studied the subject fervently. However, it didn’t seem to do the job for him. After leaving London, he declared it an expensive detour which couldn’t absolve the problem of being alive. That is where Beckett found himself when he began to read Schopenhauer. A man who, in Beckett’s own words, served as an ‘intellectual justification of unhappiness’.

The problem of being alive lured Beckett in the direction of the spiritual writings of Christian saints, which Schopenhauer also endorsed – if you replace the Christian god with an inner sense of self. Beckett was, however, met with a problem of mystical wisdom as spoke by the saints and theological servants – a problem for the unbelievers. That they promote a devotion to the spiritual realm at the expense of the earthly realm is, as we all may recognize, for the irreligious, a dangerous thing. Beckett found that this preoccupation to be at peace with one’s own god leaves one drawn more and more into isolation, apart from the people and things of the world, and serving to intensify the dread and anxiety of living a secular life.

If what Silenus says is the truth, then what if we do away with the notions of desire and happiness – a line of reasoning which Schopenhauer employed; a man who lived alone, affirming his own suffering, and constantly checking the philosophical journals to see if he was mentioned. It still seems to fall short of any answer to the fact of living, only condemning us to the reign of unhappiness. Beckett’s response, however, was not to un-affirm himself, but to find in resignation and suffering the power to create.

Beckett traveled around Europe with little success in his early literary strivings. It was in Paris that he would begin to get a hold on the haunting words of Silenus. It was here he would meet the giant figure of twentieth century literature, James Joyce – Beckett would assist him for his last novel, Finnegan’s Wake. Beckett had found in Joyce a man who was pushing to the limits the conception, and control, of knowledge. Beckett had come to realize that he could not follow Joyce’s example but needed to find a way of his own; his method would be through negation, on not knowing. He found that in exploring the world of exile, of failure and loss, there was a most precious ally. It was the great turning point in the wrestle with Silenus. It served to open a dynamic with the world which confused and delighted his audience. Although Beckett was a writer of novels, short stories, literary criticism and poetry, it would be his theatrical work which gained him international renown.

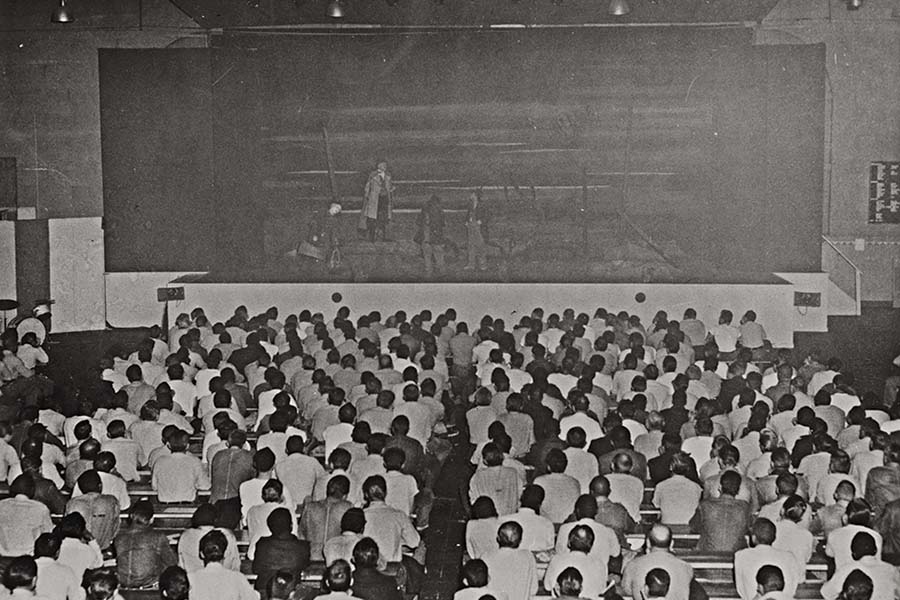

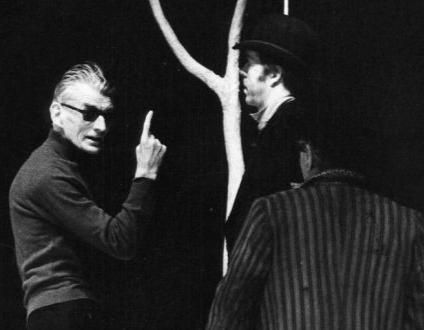

In 1953, Beckett’s play En Attendant Godot (later translated as Waiting for Godot) was met with an outcry of disbelief and laughter; critics, the former; laymen, the latter. The famous line describing the play in which ‘nothing happens, twice’ is pejorative as well as a spectacular achievement. Beckett managed to achieve that level of negation which still influences writers to this day. In 1957, the play was performed in San Quentin Prison for one night only and was met with laughter and joy by the inmates proving that Beckett’s play resounded in rich pathos. The play had manifested the language, and action, for an experience of life which could not be grasped by principles of sense-making and the acquisition of knowledge which we so pride ourselves on.

With a host of plays in the wake of Godot, Beckett refined and tapped into the idea of negation with such unabated depth that we can perceive something miraculous. It is not negation for the sake of the depressive spirit, but something much more precise. Beckett wanted an art that was tired of pretending that it could account for life, or even of overcoming life; paradoxically, his work seems to do exactly this, by admitting its failure to be able to do so. This ‘negation’ evidently fascinated, fascinates, anyone witnessing the act. The stubbornness of Beckett’s work has produced countless books on interpretation and criticism of his work which seem to forget the subtle point Beckett is trying to make. He has gone past Silenus’s wisdom that so grasped him in his youth and created his own unique vision between the question and the answer.

Life without hope is what Silenus speaks of. Beckett seems to have accepted the wisdom as a challenge for it is a recurring theme in Beckett’s work: failure, the un-knower; the no-can-do. Many of his characters are old, seemingly holding on to the last threads of life for no purpose at all; or, only to be outwitted once again by life. Worst of all, they seem to be highly self-conscious of the fact: ever questioning, ever failing. It is with remarkable courage that Beckett has written about the most daunting wisdom with such acute insight. What is more is that he has made us laugh while doing so.

It is the mastery of Beckett that he sustains the tension between the dreadful lot of humanity versus their unaccountable willingness to fail again. It may not be clear from the outline, but Beckett’s work is funny. His work, and perhaps the reason his work does sustain itself, is through the interjection of black and bodily humor; at the end of Waiting for Godot, one of the main character’s trousers fall down. There is something hilarious in the characters being placed between the impalpable nothingness of silence and Silenus’s wisdom – It is this quality of Beckett’s work that colors this in between space with beauty and laughter, somehow creating enjoyment out of the dire fact of being born.

=============

Carl Kruse Blog Homepage.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other writings by Fraser Hibbitt include The Art of Journaling, A Few Words on Coleridge, and Psychogeography.

We enjoyed this expose on Beckett in The Guardian.

Coming from Ireland I feel our two greatest writers, in a land of great writers, are James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

Count me as one of those who never understood Beckett’s popularity. A great man, surely. But I am tired of all this tiredness of the world. Roll up your sleeves and make it better, even if dust is what awaits us all.

Love that last photo of the fellow holding the Godot sign in the airport.

Isn’t he great? Thanks for stopping by!

Carl Kruse