by Fraser Hibbitt

“Glorious night to meet the lips, to do penance” spoke the cloaked figure of an elderly woman to three more veiled forms who uttered brief means of agreement. “Yes”, spoke one of them, “Yes, it is no shameful act to adhere to his presence, his immaculate darkness”. It was close by that a young man, Matthew Hopkins, happened to be lingering. The voices of the women rebounded in his capable puritan mind. “Now, Gritzelgut, my imp, find lizzie, find her now for we are soon to taste the devil!” Overcome by these frightful exclamations, Hopkins retired to his home feeling the witches presence pervade the whole house. The space in his room began to constrict and suffocate him as he contemplated the sacrilege which was taking place on his very door.

While England was being torn apart by the civil war, and the hotly disputed parliamentarian rights were being fought for, a man named Jack Stearne, from a small town located in Essex, raised a complaint to the local magistrates of an attempt on his life. It was a conspiracy of witchcraft. Hopkins, having recovered from his own terrible eavesdropping, had found the courage to leave his room and fight for Stearne’s retribution. A poor elderly woman, Lizzie, missing a leg, was brought forward on the charges of witchcraft and thrown into prison.

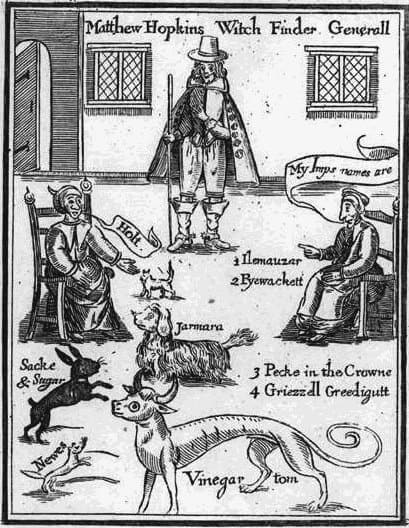

“We’ll get her confession, and, my friend, not only that, but the names of that whole wicked convent”, Hopkins spoke with a veritable confidence which so impressed the older face of Stearne. Hopkins continued: “there are ways – remember, the devil cannot confess – to force the witch to submit”. Fortunately for Stearne, these methods were easily learnt; it seems it was only brute courage that was needed to perform these methods. Lizzie was stripped naked and her body searched for the marks of her sin. Moles, extra nipples and any such oddities that imps may be suckled upon. She was pricked with blades on these sites (a test: if no blood was drawn then it was proof that an imp was suckling there). Three teats were found on her body. Hopkins, in repulsion, drew the obvious conclusion: “no honest woman, I say, would be seen with such”. However, Lizzie proved strong in courage and Hopkins felt he was wrestling the devil himself. He and Stearne kept her awake for three days without food or water. As the fourth night came upon them, Lizzie confessed. She named five other witches in the vicinity and also the truth of her five imps which did her bidding.

“Let us then find those imps”, Stearne said to Hopkins. Hopkins, though younger in years, was clearly the wiser: “the imps are nothing without their source. We must bring in those witches, we must unveil the satanic spawn”. Hopkins and Stearne wasted no time in interviewing the townsfolk pressing them to express their suspicions. Suspected witches were brought forth in an alarmingly quick succession – over a hundred from the villages. Many of the suspects quickly confessed after the sharp and diligent tactics of the two witch-hunters and the guilty lot were brought to the larger town of Chelmsford for a formal trial. All courts had been suspended due to the civil war, but an exception was made for the case of these witches. Hopkins controlled the room with poise and dignity – He had begun to wear the puritan wide-brimmed hat. In wide-eyed concentration he read out the confessions of the women and men on trial: “And this here woman, Rebecca, confessed to copulating with the devil for the last six years – that seething evil took the shape of a gentleman wearing a black cape and a pointed hat. The names of the imps: Pockniss, Alemanzer, Griddly Tearngut – names no mortal Christian could conjure up.”.

Of the many tried in court, twenty-nine were hanged in the town of Chelmsford. Many were left to the degradation of the prison where their devil-inspired powers proved impotent. A handful of witches were brought back to their local villages and hanged. Hopkins took this opportunity to speak before the crowds. Donning a cape and his black hat, he addressed the crowd: “This was no easy feat. These foul copulaters have been like the devil’s own bears raging against me, but together we can extend this sight, extend my ears and eyes by you and yours.” After the Chelmsford trials, Hopkins became a name of local fame. The puritanical population of Essex welcomed this spectacle of erudition that could root out the Devil’s lovers, and wished to help him whatever way they could.

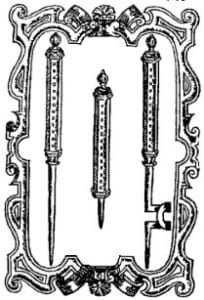

“I have here, Jack, a letter from parliament bestowing upon me the title of ‘witch-finder general’. It is my duty to these lands to purge it from this infestation”. Hopkins wasted no time in recruiting extra underlings to scour the neighbouring villages for complaints of witches which the disgruntled townsfolk had only now realized were actually witches. There, riding on his white horse, Hopkins slowly led his troupe into the towns of reported witchcraft. “It is time for to prove the case!”, Jack would announce with dead-eyed enthusiasm. “No”, Hopkins rejoined “it is time for the interrogation”. Stearne smiled and fetched the pins – Hopkins had recently given him the title of ‘witch-pricker’ to which Stearne felt an immediate boyish attachment to. They both thought it best to try their whole arsenal of interrogative techniques before either acquitting or denouncing the suspect. It was soon after Chelmsford that Hopkins applied his intellect to an old tradition of revealing a witch. He called it ‘swimming’. “It is simple. We tie a rope around the suspect, have someone hold tight and lower them into the water. We all know what outcomes we are looking for. If she floats, she is ours. A number of drownings occurred via this method but, fortunately for the two, the drowned victims were found to have extra teats and moles – incidentally proving their guilt; the only peculiar thing here was that the witches drowned instead of being hanged.

“Have the town levy a tax if they wish me to come. I am more than happy to provide my skills and put your people at ease but travel during this time is wrought with such danger and upkeep.” Hopkins was making a fine living off his campaigns. The figure of the black caped man riding with his retinue struck fears into evil’s heart. The most capable of interrogators; the most successful eye for detail. However, doubts began to be raised over Hopkins’ authority. One evening whilst having a drink with Stearne, Hopkins was approached by a local and asked if he could see the letter from parliament which had bestowed upon him his infamous title. Hopkins refused with some agitation and Stearne escorted the man away. Hopkins rode out that same evening to collect his fares.

Insistent on activity, Hopkins rode through the county urging the trials to take place and the condemnations to be ratified. Death followed in his mad meanderings. By now, Hopkins had made quite the name for himself, and quite a fortune. However, the local heads of justice grew uneasy over his vigilantism and so sent word to him that he was to stop his ‘swimming’ activities and begin official trials. The slower pace aggrieved Hopkins but his expertise and indefatigable passion still persisted. The hanging spectacle of lifeless feet came to characterize the towns of Essex and Suffolk.

“Every old, wrinkled faced, woman is a victim. Perhaps a harsh tongue or a pet cat is enough to have these innocents drawn up, humiliated, tortured and hanged”. These were the words from the vicar John Gaule who preached in his town of Great Slaughton – a town Hopkins was hoping to visit. Hopkins’ credibility was beginning to fall. The courts, reading Gaule’s sermons, began to ponder his words and wrote earnestly to Hopkins for evidence from his cases and the exact methods of interrogations which he used. Hopkins fell silent for a short spell. He rode back to his town of Manningtree where he had first heard those fateful voices exalt over their meeting with the Devil. Inspired to write a book of his activities as the witch-hunter general, he shut himself away to live again as the great persecutor. As to its reception, Hopkins would never find out – he died shortly afterwards. In their fourteen months of tireless activity, Hopkins and Stearne, with a dubious letter from parliament, accounted for over twenty percent of the witch executions which took place between the 1400s and the late 1700s.

While no one is publicly hanged these days, one can only wonder at the ongoing damage caused by superstition, misinformation and religious zeal.

==========

The blog homepage is at https://www.carlkruse.com

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Fraser Hibbitt include Van der Kolk and the Story of Trauma, After Google Glass and The Case for Dreams.

The blog’s last post was on Fernando Pessoa.

Find Carl Kruse at the Baker Labs Rosetta project. And for resources to combat superstition – the Richard Dawkins Foundation. Find me there.

Echoing, “While no one is publicly hanged these days, one can only wonder at the ongoing damage caused by superstition, misinformation and religious zeal.”

One can only wonder.

where are the hunters of the witch hunters?