by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

I have always listened to classical music, though perhaps that’s rather too vague a term for all of the wonderful varieties of music the name “classical” denotes. You know, I distinctly remember first hearing George Bizet’s “Carmen” when I was very young and being fascinated by Julia Migenes’s rendition of “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” under Francesco Rosi’s direction. Opera is quite the evocative music, most probably because of its unwavering vulnerability. The human voice is exposed in it like a lit match, leading the way for the whole of the operatic story in all its thrilling dimension.

Photo: Kawai Pianos.

My family and I went to see a double-bill of live opera streamed from the London Opera House to a cinema quite a few years ago. The two operas we saw were Pietro Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana” and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s “Pagliacci.” These two operas are often performed together, most likely because they’re only around 75 minutes each, and also complement each other thematically. They are both studies in “verismo,” the operatic post-Romantic tradition that focuses on visceral and raw emotional narratives. In essence, the Italian “verismo” translates as realism, the prefix “vero” meaning “true.” Cavalleria Rusticana is the story of a soldier, Turridu, who learns upon returning from battle that his fiancée Lola has married a man named Alfio while he was gone, so to spite her he decides to seduce another girl, leading to Lola’s jealousy and subsequent adultery with her ex-fiancée. When Alfio finds out about Lola and Turridu, he swears to commit to “vendetta” (revenge). The two men leave at the end of the opera for a fight to the death (instigated by Turrido drawing blood by biting Alfio’s ear after Alfio challenges him to a duel), and that gruesome fate falls on Turridu.

Pagliacci is a mise en abyme of sorts, a play within a play. It follows the clown Canio as he acts in his “commedia” touring troupe until his violent breakdown towards his wife Nedda as a result of her affair with Silvio. Canio stabs and kills Nedda while he and she are acting in a public performance, then proceeds to kills Silvio when he rushes on stage to help her, after which the eponymous line “La commedia è finita!” rather grotesquely concludes the opera (“The comedy is finished!”).

I cried during the whole 150 minutes of opera. The sheer strength of the voices, overpowering even the loudest of orchestral intervals, was awe-inducing. The “Intermezzo” that plays just before the fight between Turridu and Alfio has a yearning, heartbroken quality that brings me to tears every time I listen to it. Its serenity seems deceiving as a precursor to the fight between the rival men, yet the sensation it evokes of loss in the form of the howling strings harkens to the final line of Cavalleria, “They have murdered Turridu!” to which Santuzza, Turridu’s girlfriend, faints and Lucia, his mother, falls into the arms of the townswomen. The opera ends on this pained scene, of women holding one another for comfort in the face of death. My favorite song from “Pagliacci” is the lament “Vesti la giubba,” or “Put on the costume,” which recounts, in so many words, that for Canio “the play must go on” regardless of his heartbreak. The vocals in this piece are shaky, indicative of a man on the brink of tears forced to swallow his pain in order to fulfill his duty as a comic actor. It’s stunningly taken on by none other than operatic legend Luciano Pavarotti in the version I most often listen to. The piece softens, crescendos, then softens once more, as though it embodies Canio attempting to regulate his emotions before going on stage. I think the reason that these songs impact me so much is that the reason I listen to classical music is to be broken, musically, by it.

You might understand this notion in the context of heartbreak – it seems that the songs one gravitates to in states of extreme pain are aimed at heightening the pain one already feels. But even when I don’t feel sad myself, I feel there’s something essential in being moved to the point of tears by music. Classical music, including opera, make me pensive, curious, and sensitive to the most minor movements of life. I don’t always listen to music when I go on walks, but when I do, I feel as though the trees and the very ground I stand on are speaking to me through the irresistible harmonies playing in my ears. I notice the beauty of the people strolling past me, the conversations I don’t hear, the wind that soundlessly rustles the grass. I can be brought to tears from the elation of a particularly affecting climax. The level of emotivity that this music brings me can be distracting, too. If I’m working at home, like I am now, and put on some classical piece, I find my inspiration trailing away into the realm of poetry rather than the vital work I should be doing. But I love that about it. I love what it brings out in me, the quiescence and isolated appreciation that is a far departure from my everyday personality. I tend to be quite loud and brash a person. I often have an unquenchable excitement for life that means I must forever be on the move, forever working and running about, stressed and overworked. But classical music quells this aspect of me like no other music does.

I feel I must comment on my ongoing piano playing in the context of this so-called “quelling” of the stresses in my life and in my personality. I have played piano since I was 7 or 8, and I remember going to a huge piano warehouse with my father when I was around 8 to pick out a new piano for me to play on. I remember the huge mahogany beasts that sat around that big room, each with an equally blinding set of white keys waiting to draw me in and bite me into submission. We settled on a Yamaha upright, and it is such a wonderful instrument. By sheer chance, we have never had to tune the thing, despite having had it now for about 15 years. This, I’m told, is pretty rare for pianos, so I suppose we’re quite lucky.

It took a mighty long time to get to where I am now with my playing. I went through the whole ordeal of exams and endless practicing, constant replaying of pieces, frustrated days where I could barely play a note right…I recall one particular exam, my third attempt at Grade 7 with the Royal Associated Board of Music, where I came out weeping to high heaven thinking I had screwed it up again (I hadn’t, thank the Lord). But the confidence I gained from years of classical playing has meant I am now in near-total control of my musical creativity. I can sight-read like it’s a second-language to me, and if I hear a piece that I feel a certain adoration for I can learn to play it without too much difficulty (though of course this is dependent on the piece). The main difficulty I seem to face is that of dedication to one piece. I have a tendency to get excited about several pieces, then attempt to learn them all at once, which, if you happen to understand the level of complexity in a Rachmaninoff piece for example, can lead to none of these pieces ever being finished at all. But that moment where a piece falls into place, where each note drifts by without thought like the tweet of a bird being carried by the breeze, is worth every ounce of struggle. When I play a piece of piano that really touches me, one that I have been listening to for years but never thought I could even attempt, I feel like I transcend the piano and the work that has gone into learning it and fall into a deep sense of peace within myself. There is nothing quite like it. It feels mechanical, but in the most human of senses. I become a part of the piano, merely an extra limb to help it sing by itself. It is such a wonder that humans can create music.

I love the French film “Amélie.” I saw it in black and white on a video cassette the first time. It’s such a curious film, and Yann Tiersen’s delicate piano and accordion-based soundtrack brings a Parisian jauntiness and sensitivity to the beautiful love story it portrays. I actually already knew how to play the widely adored “La Valse d’Amélie” before I saw the film, but another that took my ears by storm was “Comptine d’un autre été, l’après-midi.” Yann Tiersen has all the traits of the popular classical musician; the pieces I know of his are mostly repetitive and play on variations of a single base phrase that continues the elaborate in complexity until crescendo, then peaceful end. My father said to me, “I don’t know if you’ll be able to play that last bit of the piece, it’s so fast.” Perhaps to prove him wrong, or perhaps to challenge my own limiting beliefs, I willingly took this challenge on, and learned the piece in a day. Albeit this was nothing compared to the pieces I learn now, but the joy of playing this highly aurally satisfying piece was unprecedented, for me. The last phrase of the piece is so very fast, and spans the whole of the piano, the left-hand running to-and-fro while the right caresses that familiar melody that began right at the start of the piece. It was such fun! I would play that piece so loud, thrashing the lower notes with motorized precision. Learning pieces that I had no obligation to learn, unlike those I learned for exams, brought me a newfound freedom and appreciation for classical music. I played on my own terms now.

It’s funny, when I was growing up my peers weren’t necessarily very interested in hearing what I had to play. I didn’t have any interest in learning the pop songs that some other of my fellow players would strike out on the off-tune piano in the hall of my secondary school during drama rehearsals. One boy I know would play the ‘Glee’ version of ‘Don’t Stop Believing’ every damn time he was on the piano. I may be in the minority in despising that song, but people loved it. I swiftly learned that I needed to reason with my playing, and really delve into why I was playing at all. Was it to impress others, as I knew certain pieces would, or was it for myself? There’s nothing wrong with wanting a collective appreciation for one’s art, in fact I feel that it can further one’s artistic endeavors if said appreciation is sincere enough. But if I was to continue to play throughout my entire life, I knew I had to question whether I was playing out of habit or whether the piano was a calling I felt truly drawn to, one that would bring me something other than the compliments of others.

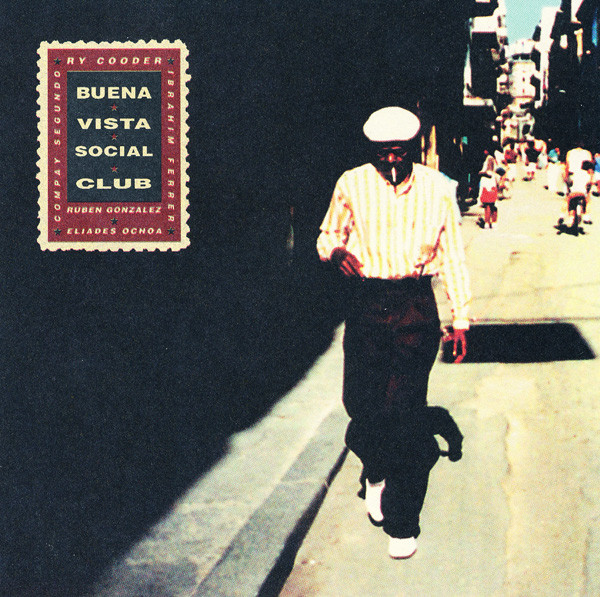

I am in the process of learning a melee of different pieces all at once. I’m not sure why I do this to myself. I am learning a piece of Spanish piano, which is much out of my comfort zone, but all the better for it as it changes up my routine approach to playing. That piece is Buena Vista Social Club’s ‘Pueblo Nuevo’, a song my parents used to play regularly from the band’s infamous self-named album.

Learning different styles of piano has been a challenge for me, one I almost gave up on for frustration at the slow pace at which I had to learn them in. I’ve been straying into boogie-woogie, stride piano, Spanish piano, ragtime, and café jazz, and boy is it exhilarating to finally scratch the surface of those seemingly unattainable rhythms! I recently learned Claude Bolling’s “Temptation Rag,” a crazily enjoyable ragtime piece that took my fancy, and when I played it at the communal piano in my local market it generated such a lovely reaction from my small audience. I took up this style of piano after witnessing the majesty of a boogie-woogie pianist at work at an evening of music and dancing at a local pub. He made me break out in disbelieving laughter at his absolute mastery of the keys, his ability to play so freely, and how he generated such a fervor in his roaringly appreciative audience.

The other pieces I’m in the process of learning are Rachmaninoff’s ‘Prelude in G Minor, Op. 23, No. 5’, a favourite of my father, and the magnificent ‘Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op 13, ‘Pathétique’: I. Grave’ from the beloved Beethoven. They’re astonishingly difficult, and perhaps that is why I must have several pieces on the go, in order to escape when the difficulty becomes too overwhelming, but I feel it is also good to overwhelm oneself in such a way. This “overwhelmingness” is aside from that of regular life stresses. It is self-inflicted, and immediately escapable should one simply walk away from the piano, but it requires dedication and a good dose of self-discipline to overcome. I feel this dedication forces me into a silent state of peace like no other activity can.

It is the purest of things to play music. I feel I understand the music I listen to so much more deeply from being personally engaged in it. Classical music has brought me the most brilliant of loves, whether that be the opera moaning in my ears or the self-induced tones of the piano keys in front of me. It is a love that demands a great deal, but that delivers just as greatly. In classical music, you love, and are loved uncountable times over.

===========

Carl Kruse Blog Homepage

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Last blog post was on saxophonist Alto Reed

Other posts by Hazel Anna Rogers include How I Fell In Love With Winter and Music, Memory and the Cloud.

Carl Kruse is also on Soundcloud.

Though classical music is not my thing, I was moved by Hazel’s writing on how this genre has touched and enriched her. Enough to go back and revisit the repertoire.

You just might find it gives back so much more compared to what you have to put in.

Carl Kruse

Classical music is my thing and I’m always surprised it isn’t even more of a thing.

I mean, I think it’s still a thing. 🙂

– Carl Kruse