by Hazel Anna Rogers

My father will often, upon hearing a song from his youth, be able to conjure up when exactly in his life he first heard the song and the emotions he attaches to it, along with word-perfect lyrics. We spoke about it once. He told me he thought it unfathomable how much space in his memory must be taken up by lyrics of songs, even songs he never particularly enjoyed but was just exposed to by friends and family. We used to sit together on late evenings, and I would watch him play song after song on our old vinyl player, blasting them into the night and reliving moments of youth in two-to-four-minute snippets. He still has all the moves from his days of disco, when he would stylishly spin and twist in a bright white suit with shining blonde locks on the dance floor.

I love to watch him dance. I feel as though people are rarely inclined, within British and American culture, to properly dance in public settings. And by dance, I don’t just mean swaying a little and tapping your foot, but really DANCE. Raves and club nights are perhaps an exception, though more often than not I see meek, repetitive foot-tappers gracing the outskirts of a madding crowd of crazed dancers. It is as though people are too embarrassed, too preoccupied with what will be thought of them should their style of dance be not to the modern taste. I think it a shame, but it makes watching my father smashing out his old routines all the more magnificent.

On our long drive down to France for our summer holiday as children, many a CD would be stuffed into any possible pocket of the car, aching to be played for the consequence of a loud sing-a-long from all corners of the vehicle. Steely Dan and Amy Winehouse come to mind as welcomely vibrant car-listening, as well as, funnily enough, Lady Gaga, an artist that my parents actually grew to love over my childhood-years obsession. ‘Poker Face’ is a particular favorite, one that my father will turn the stereo up to maximum for even in the midst of a quaint French town, to disapproving looks from the locals and quietly embarrassed encouragements from my mother to ‘turn it down’. Some of the CDs that my family own I can now no longer listen to without being reminded of those hot, stuffy moments in the car, yearning for swift arrival

The effects of sound on memory are astonishing. I know that, for myself, the impacts of music on my retrospection are most prominent in cases of love and loss. I still struggle to listen to much George Harrison or ELO without being reminded of my past lover, and for many years after it was played at my grandmother’s funeral I couldn’t listen to Debussy’s ‘Clair de Lune’ without bursting into tears. But some music brings me such joys of recollection – Steely Dan still makes me jump up and dance emphatically, my earliest memories of which are from my father’s ‘Greatest Hits’ CD that would often grace the sound system of my home, but I also associate it with my current partner, who also knows almost all of their tracks back to front. Neil Young reminds me of my childhood too, the cover of ‘After the Goldrush’ forever tattooed in my memory along with his dulcet, melancholic vocals.

Certain sounds hit just as hard in my long-term recall as songs do: a whistle or car horn will automatically make me spin my head around sharply in anticipation of my father being somewhere around, the sound of typing strangely brings me back to the sound of my brother typing away on his laptop every night, and the sound of French Moominmama speaking in the cartoon adaptation of the ‘Moomins’ will straight away make me think on my mother’s soothing words. Every moment seems influenced in some capacity by learned experience of sounds, each reaction somehow fore planned by events in my memory. All this makes me think that Sherlock Holmes’ ‘Mind Palace’ is far less unfathomable than I previously thought; we all have a mind palace of noises and sounds that build up our understanding of living.

Psychologist Matthew D. Schulkind et al published a study in 1999 of the effects of music on autobiographical memory, and the emotionality involved in the recollection of lyrics and on the factual history of the songs themselves. They found that older participants often knew more about the songs than younger participants, though I would personally suggest that this is due to the lack of musical ‘education’ around music in the 21st Century. We listen to music through headphones on streaming websites and apps, as opposed to being exposed to such programmes as ‘Top of the Pops’, MTV, 4Music, or other such outlets. Our association with music is far less physical than it was with previous generations. Buying records and CDs was, at least for my parents’ generation, the only way to have music to listen to, aside from attending events. I think this physical aspect of music challenges the unimaginable array of choice we have now. My parents would save up to buy records of their favourite artists, and I think this created a different sort of passion around artists and potentially a greater capacity for autobiographical knowledge about them than people have now.

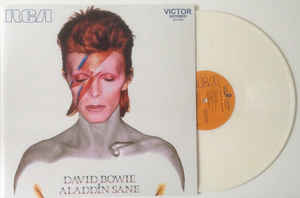

I bought CDs when I was younger and received many for birthdays and Christmas. My first vinyl record was David Bowie’s ‘Aladdin Sane’, bought for me by one of my best friends at the time. The sheer size of the thing was so very wonderful, and the delicate care with which one had to handle the disc itself so as not to damage it made it a precious thing. The act of choosing a CD or record to play from the astonishing assortment in the CD cabinet or from the vinyls leaning against it made playing the music itself far more of an event. Placing a record onto the slipmat, lifting up the tone arm, and place the metal stylus just enough away from the disc’s edge that it would neither slip off nor start a song halfway through, was a theatre in itself. To watch the disc spin around was a mesmerizing affair too.

I think we’ve lost touch with our memory of music due to the proliferation of technology and its endless capabilities. I grew up listening to story tapes or story CDs at bedtime, many of which I can still quote by heart with my twin years later, and we would argue about which to put on, partially because my sister would fall asleep slower than me and thus have to listen to more of the story than I, so she may have been justified in wanting her way. Now, I suppose, there is no need to argue. One can simply put in earphones or pop in some Bluetooth EarPods and no-one need be any the wiser as to what the other person in the room is listening to.

This all sounds bitter, and I think it’s easy to glorify bygone days when your own present seems lacking. I do love online music platforms, like Spotify. I listen to songs on it constantly and often find great new music that I would otherwise not have been exposed to. I listen to such brilliant podcasts on there, which make walking into my loud town centre far more intellectually absorbing than it would otherwise be. But I am grateful for the evenings I spent with my father changing records around, and the nights we spent watching Top of the Pops and laughing at the poor graphics and often even poorer acts that sometimes graced it. It made music a more rounded experience, something more significant than just popping in some headphones and pressing ‘play’ on a random playlist. I took up the ‘Top of the Pops’ tradition with my old housemates. We used to flip between the Food Channel, and laughing at the American presenters and their greasily excessive recipes, and Top of the Pops, where my housemate Maria and I found the anthem of our friendship: ‘I didn’t mean to turn you on’ by Robert Palmer. It felt good to share this experience with them, like I was conveying some aspect of my memory into theirs so we could share it and I could keep it going after leaving home. Every time either of us put that song on it would immediately make us laugh. I have a video that Maria sent me of myself stood outside our kitchen window, pretty inebriated, smoking, and mouthing the words to Palmer’s now-infamous tune.

Sound and music are well-accounted in their ability to trigger memories. In Robert Graves’ memoir he depicts his struggle with ‘shellshock’, a common form of post-traumatic disorder caused by constant exposure to bombing, shelling, and gunshots during wartime: ‘the noise of a car back-firing would send me flat on my face, or running for cover’ (page 237, Goodbye to All That). Kurt Vonnegut’s pitiful protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, is overwhelmingly triggered by the musicians playing at his eighteenth wedding anniversary, and experiences ‘powerful psychosomatic reactions to the changing chords’ his ‘mouth [filling] with the taste of lemonade, and his face [becoming] grotesque’ (both chapter 8). He later realises these reactions were results of his harrowing experience of the bombing of Dresden during World War II.

Memories elicited from sound, or music, are called ‘echoic’ memories. Auditory information is collected upon hearing a stimuli so the brain can understand its meaning. Usually, echoic memory is rather short lived. But how is it then that we recognise the sound of our friends’ voices, months after we last heard them speak? Repetition of sounds constantly over time render them important enough to store in auditory long-term memory. The sound of a kettle boiling, of pasta bubbling over onto the stove, the opening of a fridge door, sequences of notes in a piece of music…all these noises are stored so the brain can navigate the sounds of human life, and in the case of music, differentiate between a set of random noises and the pattern of harmonies and textures that produce a piece of music. Fascinating, isn’t it?

There is something about the sheer proliferation of music in the 21st century that has changed how we absorb and appreciate music itself. Whereas before we actively sought out music, we are now so surrounded by it that escaping it has become a feat in itself. Supermarkets, clothing stores, television, restaurants, cafes…everywhere we go we are surrounded by bad, overbearing reproductions of music. It seems rare to find somewhere without music playing in the background. This trend of ‘background listening’, to me, has decreased the value of music, and made me appreciate quiet environments far more. Sometimes, my only interaction with music in a day is when I play my piano. During these endless days of Covid-19, I find myself longing for live music, for the jazz and blues I would go and listen to in the bars and pubs of Brighton, for the sub-par open-mic nights, for the classical concerts I would go and cry to. I don’t want to listen to my damned earphones anymore. I don’t want to listen to the grainy crackles of department store sound systems. I miss the times when music was tangible, sociable, and, above all, good quality!

I’m sure those times will be back again soon, probably sooner than we know. In the meantime, I’ll keep playing my piano and keep (begrudgingly) listening to music through my little red earphones. In the end, I’m grateful that we have music at all during this time. A good song can lift my spirits more than any words could, and I’ll always be thankful for that.

=======================

Carl Kruse Blog Homepage

Contact: carl AT carlkruse.com

Other writings by Hazel Anna Rodgers: here and over here and another.

More on Hazel Anna Rodgers: https://badessay.com/

Speaking of music, if you are on Soundcloud stop by and say hi at Carl Kruse Soundcloud.

Like the author’s dad, music for me is often a time machine back to a better and happier place.

Isn’t that often the case for all of us? 🙂 Thanks for stopping by Twainer.

Carl Kruse

I really enjoyed this post. Thanks Hazel and Carl.

Oh hey! Thank you Mithrandir Jones!