by Hazel Anna Rogers for the Carl Kruse Blog

The water is of the brightest hue. She is almost royal blue, so jubilant is her shade. No current nor wind moves her, and she remains most still and peaceful as the dance begins.

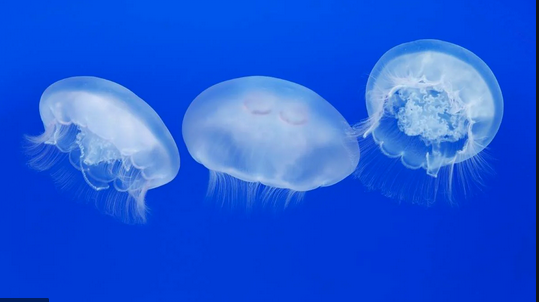

Gentle tendrils, mermaid’s hair, whispering like grass blowing in a breeze, or cherry blossom quivering on a spring branch. These ethereal lengths are attached to bulbous ochre heads that pulsate and fan out as they move around in the water. They are like skirts blowing up in streets when storms rage in from the west. The heads bump softly into one another at times, but they make no sound. They move hypnotically, gracefully, silently.

These creatures, of the genus Chrysaora, are known by the name Pacific Sea Nettles. They cannot kill you, or, at least, they are unlikely to, but they will cause a sharp nettle-like stinging pain should you stray too near to their long pink tentacles.

I watch them dance on screen, safe in the knowledge that I am far from the Pacific waters that harbor these prolific throbbing orbs. There is something about jellyfish that fascinates me and equally terrifies me. In the section of the English Channel that joins Brighton I have seen, and been stung by, the translucent and pink Moon Jelly and the tiger-striped beige-white Compass Jelly. Nothing quite compares to the moment when one peeks below the water and sees, whether in the distance or too close for comfort, the pulsing body of a jellyfish edging nearer, brought in by the tide. Despite me knowing that I am unlikely to suffer great consequences from such an encounter with this foe, I am significantly more frightened by jellyfish than by sharks, which are probably more dangerous on the whole.

The video that I am watching is accompanied by a soothing soundtrack of binaural echoes and sounds. This music, along with the slow movement of the jellyfish over the square video screen, are enough to send me into a trance. It is meditative to watch these strange animals glide over a screen, oblivious to the fact that they are being watched. This is a video captured by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, a non-profit conservation company whose aim is to make accessible the beauties and intricacies of the ocean while playing their part in efforts to preserve the ocean around California and wider afield. (To see the Pacific Sea Nettles in all their glory check out the live cam at https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/live-cams/jelly-cam).

The aquarium opened 37 years ago and has since been awarded a prestigious accreditation from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums and even appeared in the movie Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. In 1989, the aquarium released their first otter back into the wild, which they had raised from stranded puphood. The Monterey Bay Aquarium has continued to pioneer in the rehabilitation and research of the sea otter population around the California area since their first home-raised otter was released.

I have never been particularly ‘for’ aquariums or zoos, mainly for the reason that the majority that I have either visited or learned about (Sea Life in Brighton and elsewhere and Chester Zoo in the north of the UK) to me embody everything that I deem to be wrong with the interaction between humans and other life on earth. These two establishments seem primarily to thrive not through the conservation nor rehabilitation of the animals they exhibit, but through the monetary gain that they receive from bringing in millions of customers a year to gawp and point at animals behind glass and walls, animals that sit depressed on plastic rocks and who wither away in tiny containers. But the Monterey Bay Aquarium is quite another story. For example, when, in 2004, the aquarium showcased their first young white shark (one of many who would grace the aquarium during the next decade) in their million-gallon Open Sea Exhibit (which is where they harbor the majority of the sea creatures they study), they released the beast back into the ocean with tags on it a few months later. This process both enabled the aquarium to learn the best they could about shark(s) in captivity while simultaneously being able to pursue the natural movements and traits of these animals in the wild.

The sea is big. I mean quite absurdly big. 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, with 95% of this water being sea water. A meager 5% of the ocean has been explored by humans. Despite our rather poor attempts at proper sea exploration, scientists (detailed according to an article on theatlantic.com) have come to the conclusion that only about 20% of Earth’s species live in water (15% in the ocean, and 5% in freshwater); just to note, these statistics do not refer to microbial diversity such as single-celled organisms. Robert May, an ecologist at Oxford, suggests that the disparity between the sheer number of species found on land compared to the apparently sparse numbers in the oceans and rivers of Earth is due to the lack of physical barriers in the ocean keeping populations apart from another. The land masses of Earth are spread out and thus encourage diversity in the fact that animal populations must evolve separately from each other. A further factor of species diversity on land is the quantity of very different ecosystems that enable different kinds of life to thrive and others not so (such as the desserts of northern and central Africa, the cold desserts of Siberia, and the great tropical weather patterns of the Galapagos). Also key to mention is the paltry supply of insects that live in the ocean. There are believed to be around 10 million species of insect on Earth (of which we have only discovered around a million). Only around 3% of all insects have aquatic/aquatic larval stages (scholarship.org). There are (approximately) some 1.4 billion insects per human on the planet, and insects make up near to 90% of ALL species on Earth, and more than half of all living things! These statistics may make the facts about the sparsity of ocean life less shocking.

It is quite strange to me that humanity chooses to explore space over its own planet (Though the Carl Kruse blog loves the ideas of both oceanic and space exploration – Carl Kruse). While I understand the psychological implications of journeying afar and exploring the unknown (in the form of space travel) because these journeys may make us feel more connected with our place in the universe, it befuddles me to think of how little we know about the oceans that surrounds us.

I have watched the video of the Pacific Sea Nettle jellyfish bobbing around quite a few times now. It is a comforting and calming sight. Perhaps that is was frightens people about the ocean. All the loudness and noise and destruction that a rocket produces when it explodes before lift-off is lost, down here, in the depths. How quiet the world seems when one dips one’s head below the waves. I remember the height of summer in Brighton, when the beaches and shorelines were so packed that I could barely socially distance, even in the water. I remember strapping my goggles to my head and swimming far out, almost beyond the pier, and then dipping my head below the water, blowing out bubbles from my nose so that I would go deeper in. It is so black down there, so dark and fearsome. I doubt myself when I look down into that blackness, I doubt everything that I am. But it is so, so quiet when one leaves the mainland and lurks below. One might forget that one is on Earth, should one stay down a moment too long.

On one particular occasion, when I had swum out for some time, I looked into the beneath and saw a moon jellyfish floating just below the surface of the water. Panicked, lurched upwards to take a breath and swam as fast as I could towards the shore. Terrifying is the sea.

==============

The Carl Kruse Blog homepage is at https://www.carlkruse.com.

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com.

Hazel Anna Rogers last wrote about being lonely.

Another Carl Kruse blog, which focuses on nonprofits, wrote about the Monterey Bay Aquarium, here and over here.

You can also find Carl Kruse on his other blog.

I would love to see jelly fish some time.

I love jellyfish. Not getting stung of course. But their peaceful, lulling nature.